-

-

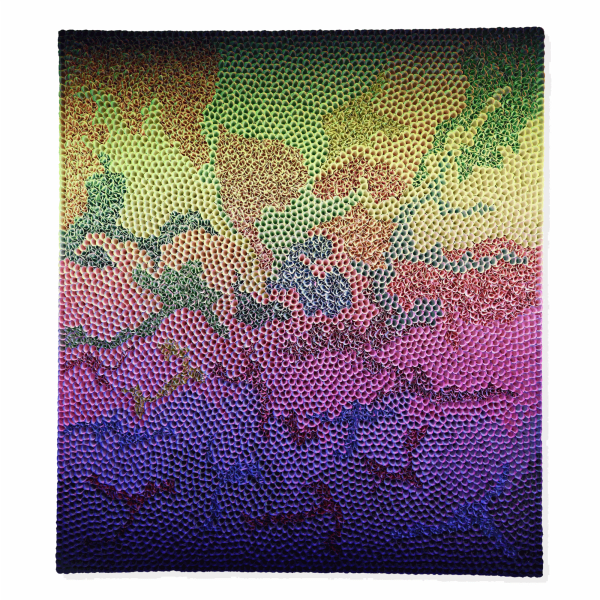

Ilhwa Kim

SOUTH KOREAIlhwa Kim (b. 1967 in South Korea) creates works that are composed of tens of thousands of seed units. Each seed unit has a combination of straight lines and circles,... -

Sougwen Chung

CanadaSougwen 愫君 Chung is a Chinese-Canadian artist and researcher, and is the founder and artistic director of Scilicet, a London-based studio exploring human & non-human collaboration. Chung is a former... -

Zheng Lu

ChinaZheng Lu (born 1978 in Inner Mongolia, China) works and lives in Beijing. Zheng Lu studied at Lu Xun Fine art Academy from 1998-2003 and then at the prestigious Central... -

Vladinsky

RomaniaVladinsky was born in July, 1988, in the city of Onesti, a city located in the Moldovan area of Romania. From the first years of school he was fascinated by... -

Joseph Klibansky

NETHERLANDSJoseph Klibansky (b. 1984 in Cape Town) is a Dutch artist based in Amsterdam, Netherlands. His work examines the relationship between a thing and its essence, between what we see... -

Zhuang Hong Yi

CHINABorn in 1962 in Sichuan Province, China, Zhuang Hong Yi lives and works between The Netherlands & Beijing. Zhuang's well known and highly collected 'flower bed' works are crafted from... -

Jan Kaláb

CZECH REPUBLICJan Kaláb became a prominent figure on the urban art scene after emerging from former Eastern Bloc. In the 1990s he established an iconic crew 'DSK', which proved instrumental in... -

Maja Petrić

Lumen Prize-winning artist Petrić masterfully combines art, technology and real-time data to depict nature’s fragility. Her sculptural installation Specimens of Time: Hoh Rain Forest (2025) part of the Specimens of... -

Eser Gündüz

TURKEYEser Gündüz is an emerging artist whose work is focused on researching the concept of historical utopias and relating it to our time, creating work that reacts to the different... -

Camille Hannah

AUSTRALIACamille Hannah’s work predicate a model of painting that is born from within the frame of technology; they are embedded in twenty-first century gestural abstraction while conceptually vested in digital... -

Max Patté

New ZealandAt its core, Max Patté’s practice is an exploration of the infinite qualities of light and how it is expressed in the natural world manifested into physical works in the... -

Anne von Freyburg

NETHERLANDSAnne von Freyburg (b. 1979) is a Dutch artist based in London. She received her MFA from Goldsmiths (2016) and holds a BA in Fashion Design from ArtEZ Arnhem, The... -

Owen McAteer

IrelandOwen McAteer (born 1986) is a Northern Irish visual artist based in Madrid. A generative artist & creative coder his work revolves around algorithms and mathematics to discover the hidden... -

Jason Sims

AUSTRALIAJason Sims is an Australian artist who works in the realm of perceptual art. Using the properties of light and reflection, he creates simple illusions of space in the form... -

Romina Ressia

ARGENTINABorn in 1981 in Argentina, in a small town near Buenos Aires. Her passion for art started at a young age but it was not until her late twenties, after... -

Julian Voss-Andreae

USAJulian Voss-Andreae, a German sculptor based in Portland (Oregon, USA) is widely known for his striking large-scale public and private commissions often blending figurative sculpture with scientific insights into the... -

Gordon Cheung

UK | HONG KONGGordon Cheung is an internationally acclaimed multi-media artist who was born in 1975 in London to Chinese parents. His work is found in major museums including The British Museum in... -

Seungwan Park

South Korea -

Ayobola Kekere-Ekun

Nigeria -

Ryosuke Misawa

Japan -

Mary Ronayne

IRELANDIrish painter Mary Ronayne elevates comedy, wit, and fun to a level of purpose, paving the way for farcical elements like melting faces and candy pop colours to become celebrations... -

Wang Ziling

CHINA -

Hannes Schauer

Austria -

Lyès

FRANCESeduced by the whole existence and the love of the universe, Lyès celebrates the energy of life. Inspired by mindfulness and spirituality, the artist is attracted by reality and our... -

Retna

USA -

Gianfranco Meggiato

ITALYGianfranco Meggiato was born in Venice in 1963, where he attended the Istituto Statale d'Arte art college for five years, studying stone, bronze, wood and ceramic sculpture. At the invitation... -

Angela Santana

Switzerland -

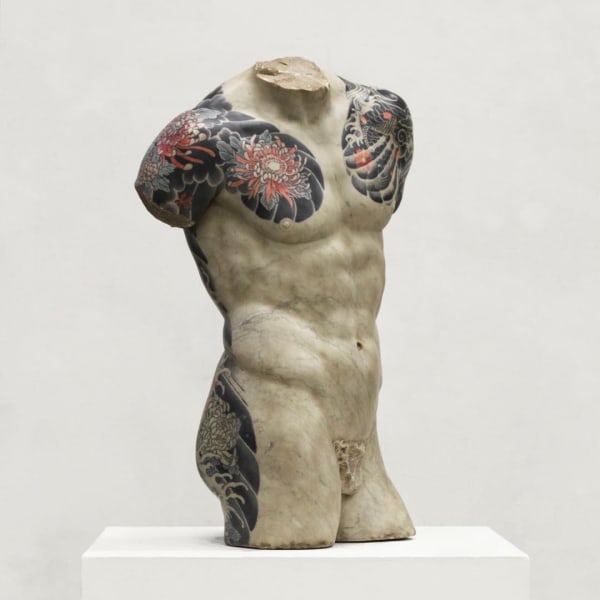

Fabio Viale

Italy -

Igor Dobrowolski

PolandIn the process of discovering myself, I have revealed some strong psychological figures (inner child, feminine side, tyrannical side, contemporary side). I noticed that some paths went entirely differently when... -

Alejandro Monge

Spain -

Dean Fox

UK -

Sophie Victoria

AUSTRALIA -

Gao Xintong

China -

Li Jie

China -

Stefan Stanojevic

Serbia -

Damien Bénéteau

France -

Lucile Gauvain

France -

Katya Zvereva

RUSSIA -

Kostas Papakostas

Greece -

Cynthia Sah

China -

Jade Ching-yuk Ng

China -

Orlanda Broom

United Kingdom -

Hunt Slonem

USA -

Lise Stoufflet

France -

Christian Hiadzi

Ghana -

Dong Li-Blackwell

China -

Mark Posey

USA -

Pan Jian

ChinaInternationally recognised Pan Jian (b. 1976 in Shandong Province, China) has been acquired by major collectors such as Uli Sigg and DSL Collection. Pan Jian conjures up elements from the... -

Sepand Danesh

Iran -

Iryna Maksymova

Ukraine -

Lu Luo

The Chinese artist Lu Luo, married to artist Zhuang Hong Yi, received her artistic training at the Sichuan College of Fine Arts in Chongqin. In 1992 she and her husband...

-

Keep up-to-date with our Programme.

Subscribe to our mailing list to get the latest news on upcoming exhibitions, collaborations and events.

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy (available on request). You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.